By Christan Griffin, M.Ed., BCBA, LBA

Prompts are a foundational procedure widely used in the field of Applied Behavior Analysis; however, prompts are used by everyone, everyday across many individuals ranging in age, cognitive abilities and developmental levels. Simply put, prompts are a way of teaching a new skill to someone, with the ultimate goal for the skill to be performed independently one day. Whether you are learning codes to a new computer software, learning to brush your teeth, or learning how to use a prompt hierarchy, each of these skills require teaching using prompts that are individualized to the skill being taught and the individual who is learning the task. This is no different for children and adults with developmental or cognitive disabilities who require additional support when learning new social, communication and daily living skills that will help them to function independently and successfully across the day. The purpose of this article is to demonstrate the continuum of the prompt hierarchy and provide examples of how it can be utilized creatively across many different skills.

Benefits of Learning with Prompts

Correct responding through the use of prompts, amplifies access to reinforcement for the desired response, which strengthens the target behavior in the presence of the Discriminative Stimulus (i.e., Sd, the instruction, environmental cue etc.). In other words, prompts are incredibly helpful when teaching a skill because it allows the learner to know exactly what response is required and what the benefit will be (e.g., break, praise, snack). Errors can result in a lower rate of reinforcement for each attempt which may further impede learning (Myrna, Weiss, Bancroft, & Ahearn, 2008). Think about a time when you were learning a new or extremely challenging skill. What level of support did you require to be successful? How was the support, or prompts, provided and which did you find most helpful when learning the task? Now imagine you the task instruction was provided without any guidance or instruction. Let’s pretend you tried multiple different avenues to teach yourself this skill but failed at each attempt. Most would agree this would cause a great deal of frustration and significantly interfere with the motivation to learn the task, and potentially future tasks as well. Using prompting hierarchies when working with individuals diagnosed with cognitive or other developmental disabilities are instrumental for the learner. Research has noted how prompts reduce frustration and provide assistance when learning a new or challenging task. Minimizing errors may also reduce the likelihood of problem behavior during instruction (Weeks & Gaylord-Ross, 1981). The likelihood of success is dependent on effective teaching strategies throughout the learning process, one of the most valuable being prompts.

Prompting Procedure Defined

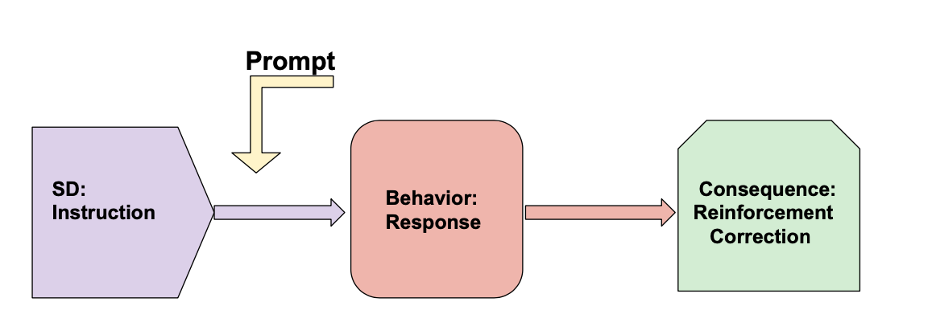

Prompts are tools to assist with the acquisition of new skills or aid with increasing independence of skills inconsistently demonstrated. Prompts can be considered antecedent strategies or preventative strategies, which reduce the likelihood of incorrect responses and increase the frequency of the desired response. An example of the three-term-contingency is asking the learner to wave to a friend (Sd), the learner waves (response), and then is provided with praise as a consequence (reinforcer). However, if the student cannot consistently and independently respond to the instruction wave, a prompt (e.g. modeling the action of waving) can be used to evoke correct responding (Cengher, Budd, Farrell, & Fienup, 2017). The below chart demonstrates the three-term contingency, Antecedent, Behavior, Consequence (ABC) in relation to introduction of the prompt.

Types of Prompts

Stimulus Prompts

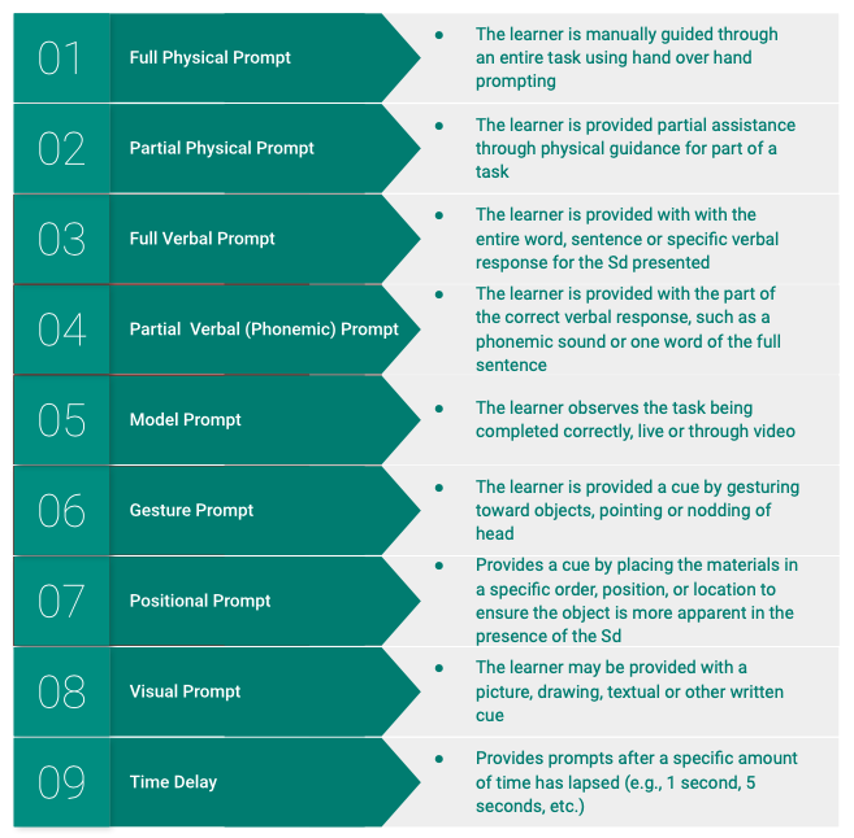

Prompts, when coupled with the discriminative stimuli (i.e., the cue or instruction), are supportive antecedent strategies which encourage learning, promote independence and build confidence that empowers learners. There are many different types of prompts separated into two main categories, stimulus- and response-prompting. Stimulus prompts are implemented when the presentation of the instruction or cue is manipulated and will occur concurrently within the stimuli. Some examples include exaggeration of the size or color, modifying the location, or even placing highlights or stickers on the stimuli itself to provide the prompt within the stimuli. An example of this would be if a learner is being taught how to use a timer. Placing a green sticker on the minute button and a red sticker on the start/stop button will prompt the learner to push the correct button when instructed to set the timer. Stimulus prompts are primarily presented within the prompt subgroup of visual prompts, including positional, pictures, and some textual prompts.

Response Prompts

Response prompts, unlike stimulus prompts, are when prompts are presented in addition to the instruction or cue to evoke correct responding. The main difference being that the prompt can be presented at different times during the learning trial (Deitz & Malone, 2017). Both categories enable the provider to tailor instruction specifically to the style of learning for each individual learner (Demchak, 1989). The majority of response prompts are typically going to fall within the prompt subgroups for physical guidance, gestures, modeling/video modeling and verbal prompts. An example of a response prompt would include providing the instruction, followed by an immediate prompt or simultaneously prompting with the instruction. For example, if a child is learning to follow an instruction to roll a ball across the room, the provider would state the instruction “roll the ball”, while simultaneously using a physical prompt to have the child’s hand roll the ball forward. Thus, the instruction is stated at the same time the ball starts rolling. Another example would be teaching a learner to answer the question, “What is your name?”. The provider would state the question, followed by immediately stating the answer to the question using a full verbal prompt. This example demonstrates how a prompt can be provided at different points of the learning trial. The table below defines some of the more commonly utilized prompts to teach discrete skills and behavioral chains involved in a task.

Prompt Hierarchy: Most-to-Least Prompting Procedure

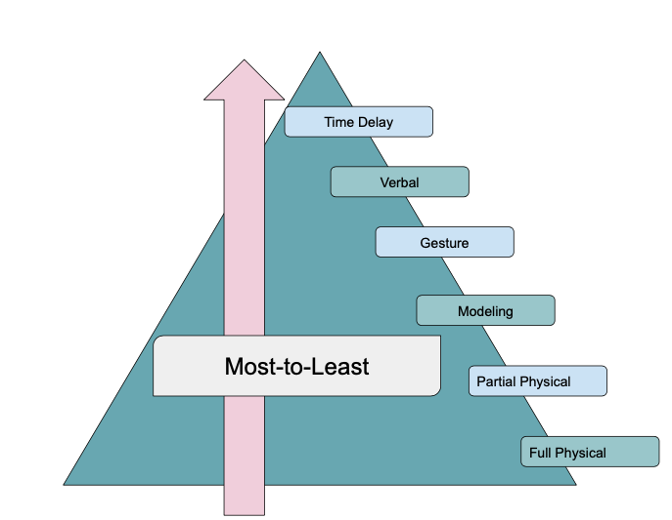

Most-to-Least

Most-to-Least prompting involves teaching a skill by starting with the most intrusive prompt to ensure the learners contacts the correct response and reinforcement, while also reducing errors. The intrusiveness of the prompts are then systematically faded across trials if the learner is demonstrating success. Most-to-least and Least-to-Most prompting procedures can be utilized with discrete trial teachings, as well as teaching successive steps to a task, such as brushing teeth. Additionally, these strategies can be utilized to teach a chain of tasks, such as completing a morning routine (i.e., breakfast, shower, dressing, etc.) (Cengher, Budd, Farrell, & Fienup, 2017).

Listener Discrimination Discrete Skill

An example of most-to-least prompting for teaching a learner to hand over a toy car when asked may include beginning with the most intrusive physical prompt (e.g., hand over hand) and manually guiding the learner’s hands through all steps until completion. Once the learner is demonstrating success with the most intrusive physical prompt, fading to a lesser intrusive physical prompt would be employed for the next learning trial. The prompt hierarchy for this skill would essentially fade from full physical, partial physical, gesture, time delay and independence.

Expressive Language Discrete Skill

If the skill requires no physical efforts, such as learning to label stimuli in the environment, then the most-to-least procedure can be utilized using verbal prompts such as full verbal, partial verbal, textual, as well as time delay and gesture prompts.

Example 1:

For instance, if teaching a learner to say, “Cat” when presented with a picture of a cat, the prompt hierarchy may resemble the following: Full verbal prompt (“Cat”), Partial Verbal (“Cah”), Time delay 2 seconds, Time delay 5 seconds, and independence.

Example 2:

Moreover, if the learner is increasing the length of utterance when manding, a prompt hierarchy may include the following: Full verbal (“I want cookie”) paired with textual script reading “I want cookie”, then faded to textual script “I want____”, moving to a partial verbal prompt (e.g., “I___”), gesture prompt (e.g., expectant look, shrug shoulders), time delay 5 second and independence.

Graduated Guidance

When using Graduated Guidance prompts the skill would be taught using prompts within the physical continuum only (e.g., full, partial physical, no prompt) (Cengher, Budd, Farrell, & Fienup, 2017). Graduated guidance can be used to teach skills such as appropriate use of utensils during mealtime. For example, using most-to-least graduated guidance for learning to use a fork would include the following sequence of prompts: full physical prompts (hand-over-hand), partial physical prompt one (prompt at the wrist), partial physical prompt two (prompt at the forearm), partial physical prompt three (prompt at the elbow), followed by independence (i.e., no-prompt) (Demchak, 1989).

Prompt Hierarchy: Least-to-Most Prompting Procedure

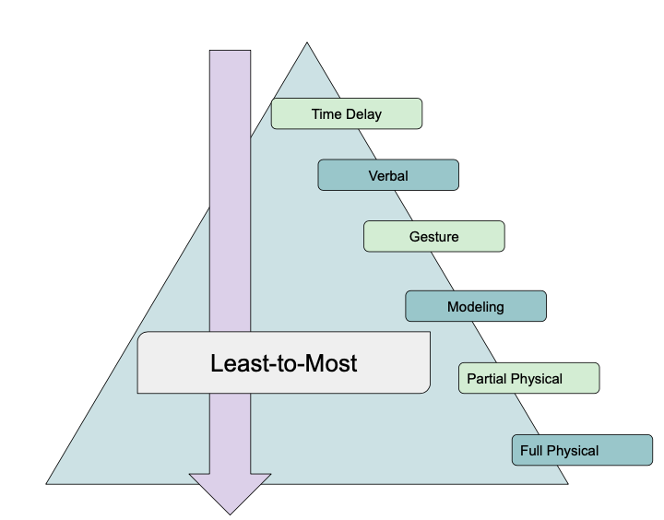

Least-to-Most

With least-to-most prompting the learner is provided with an opportunity to independently respond to the instruction. If the learner engages in no response or an incorrect response a more intrusive prompt will be provided at the next trail presentation. The intrusiveness of the prompt systematically increases with each learning trial until the learner engages in a correct response (Cengher, Budd, Farrell, & Fienup, 2017).

Listener Discrimination Discrete Skill

For example, if the instruction “sit down” is being taught, the prompt hierarchy may include the following: time delay 5 seconds, positional prompt (moving chair next to learner), gesture prompt (pointing to the chair), model prompt (teacher sits in chair), partial physical prompt (manual guidance from the shoulders) and full physical. The intrusiveness of prompts would systematically increase until a correct response is evoked (Neitzel & Wolery, 2009).

Expressive Language Discrete Skill

The least-to-most prompting procedure can also be implemented across expressive skills such as tacting, intraverbals and manding. For instance, the learner is working on asking for a cookie. The prompt hierarchy may include prompts such as: time delay 3 seconds, provide gesture prompt (e.g., shrug shoulders and put both palms of hands up), verbal prompt (e.g., “Did you want something?”), partial verbal prompt (e.g., “Coo”), and ending with a full verbal prompt (e.g., “Cookie”).

Summary

In summary, effective and efficient prompt hierarchy and prompt-fading procedures have many advantages when teaching a variety of tasks, including new and difficult skills, or simply improving the thoroughness and independence of a partially learned skill. Utilizing prompts has proven to create success for the learner when procedures are implemented with fidelity, individualized to complement the particular skill, and while ensuring to incorporate individual learning styles. Moreover, keep in mind the main objective of prompt hierarchy and prompt fade procedures is to produce the highest level of independent correct responding with the least amount of resources (Myrna, Weiss, Bancroft, & Ahearn, 2008). Increasing an individual’s level of independence is incredibly advantageous for their future well-being. Independence has the ability to open doors for meaningful opportunities in the future. In essence, independence can really be thought of as freedom; freedom that will harvest a meaningful and high quality of life for years to come.

About the Author:

Christan Griffin, M.Ed., BCBA, LBA

Christan Griffin, M.Ed., BCBA, LBA has worked closely with neurodiverse learners in a variety of settings for over a decade now. Christan began her career in 2009 working 1:1 with a child diagnosed with Autism. This experience sparked a passion that ultimately led her to pursue her master’s degree in Special Education and certification as a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA). Christan has experience with curriculum development and program implementation for ages ranging from 18 months to 30 years old across individuals diagnosed with Autism, as well as many of the common comorbid conditions. Christan currently serves as the Interim Director of Training, Clinical Supervisor, and a Senior Clinician at Behavior Change Institute. Her responsibilities include development of BCBA supervision and training content, providing direct support and consultation for BCBAs, and case management for the Adult population. Outside of her daily clinical responsibilities, she is currently serving as a stakeholder on a committee conducting research through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), and has recently published on telehealth implementation of ABA treatment in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. Christan has a 12-year-old son who was diagnosed with Autism at the age of 2. The personal experience coupled with her clinical experience, continues to fuel her motivation to invest time and increase knowledge in the field of Applied Behavior Analysis.

References

Cengher, M., Budd, A., Farrell, N., & Fienup, D. (2017). A Review of Prompt-Fading Procedures: Implications for Effective and Efficient Skill Acquisition. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 155-173.

Cooper, J. H. (2007). Applied Behavior Analysis (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

Deitz, S. M., & Malone, L. W. (2017, June 12). Stimulus Control Terminology . The Behavior Analyst, pp. 259-264.

Demchak, M. A. (1989). A Comparison of Graduated Guidance and Increasing Assistance in Teaching Adults with Severe Handicaps Leisure Skills. Education and Training in Mental Retardation, 45-55.

Myrna, L. E., Weiss, J. S., Bancroft, S., & Ahearn, W. H. (2008). A Comparison of Most-to-Least and Least-to-Most Prompting on the Acquisition of Solitary Play Skills. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 37-43.

Neitzel, J., & Wolery, M. (2009, October). Septs for Implementation: Least-to-Most Prompts. Retrieved from National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders: https://autismpdc.fpg.unc.edu/sites/autismpdc.fpg.unc.edu/files/Prompting_Steps-Least.pdf

Weeks, M., & Gaylord-Ross, R. (1981). Task Difficulty and Abberrant Behavior in Severely Handicapped Students. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 449-463.